The Promise of Nuclear: Part I

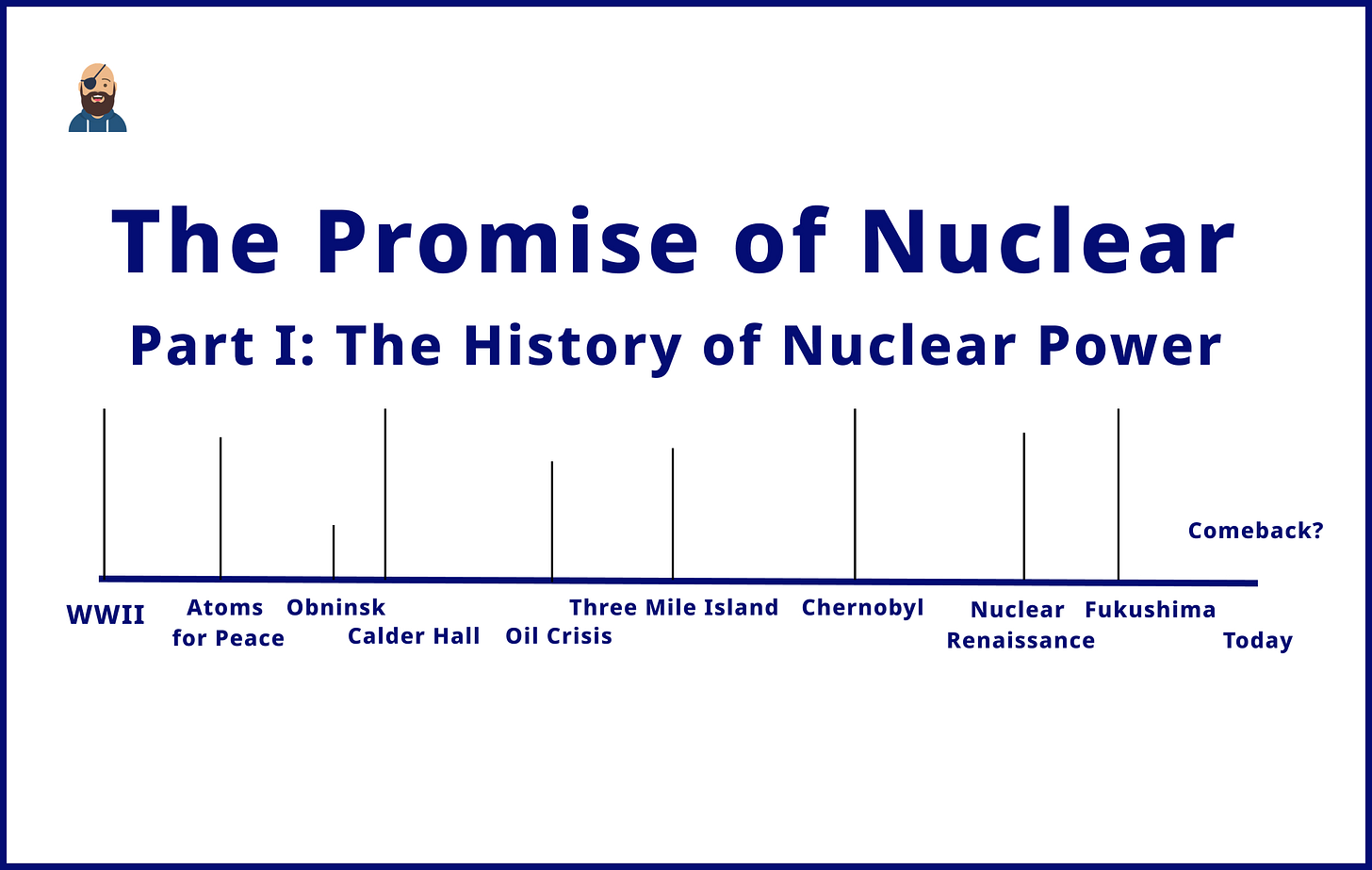

The history of nuclear power

This is Startup Pirate #105, a newsletter about technology, entrepreneurship, and startups every two weeks. Made in Greece. If you haven’t subscribed, join 6,370 readers by clicking below:

The Promise of Nuclear: Part I

The history of nuclear energy is marked by a pursuit of scientific knowledge, economic progress, unfortunate events, and propaganda. In the aftermath of World War II, everyone was talking about the destructive capabilities of the atomic chain reaction and the military advantages it could provide. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki marked the end of the war. But what changed the climate was a speech by the US President Eisenhower in December 1953 at the United Nations called “Atoms for Peace”:

“This greatest of destructive forces can be developed into a great boom for the benefit of all mankind”.

The narrative was quickly internationalised. Governments and energy companies worldwide rallied behind it and that would change the way people talked about nuclear energy. Developing civilian reactor programs to produce electricity was suddenly seen as a global beacon of progress. Countries wanted to take in the development of this new, gleaming future. The best and the brightest worked on bringing economic nuclear power to homes and the industry.

The Obninsk Nuclear Power Plant in the Soviet Union was the world's first nuclear power station to generate electricity for the power grid in 1954. It took another two years for the first full-scale power station to begin operations in Calder Hall, North West England (though its primary purpose was likely to produce plutonium for the UK's nuclear weapons programme). It was such a manifestation of national progress that the Queen herself came to perform the ceremony of the big switch-on:

“This new power, which has proved itself to be such a terrifying weapon of destruction, is harnessed for the first time for the common good of our community”.

Others were not far behind them. In 1957, the US opened the Shippingport reactor as the country's first commercial reactor. Through a series of events, like the 1973 Oil Crisis, when the price of oil quadrupled, countries ramped up the build-up of nuclear power plants. Over the following decades, France embarked on the most ambitious nuclear program ever, constructing 58 nuclear power reactors, ending up with 75% of its electricity coming from them. The US built 104 reactors and got about 20% of its electricity (or 50% of its carbon-free electricity) from them.

While Greece was one of the twelve founding Member States of CERN in 1954, it formally entered the Atomic Age in 1961 when the Nuclear Research Centre, “Demokritos”, began operating a reactor. Achilles Hekimoglou, author of the book “Atomic Era: Nuclear Energy, Reactors, and Uranium in Greece in the 20th Century” says that at that time, the Greek government, in collaboration with the public power corporation, wanted to make the country reliant on nuclear by 50% of its energy demands.

But the industry was in for some unfortunate surprises. Three Mile Island, Pennsylvania (1979) and Chernobyl, Ukraine (1986). While Three Mile Island was officially recorded as an accident where radiation released never reached levels dangerous to humans and the death toll was zero, the projections about Chernobyl were catastrophic: 31 people were killed during the accident, and 9,000 cancer-related fatalities in Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. Both of them were significant turning points for the development of the industry but, most importantly, for the public's perception of the health and safety risks. An anti-nuclear sentiment grew worldwide. Chernobyl also marked the end of Greece’s short-lived nuclear program.

While labour shortages, construction delays, and tighter regulations had relatively slowed down growth, a new narrative push brought nuclear once again to the forefront of the political agenda. In the late 1990s and 2000s, the safety record of the Western commercial reactor fleets and smooth operation of reactors combined with ongoing worries of global climate change due to carbon emissions brought about substantial talk for starting up new builds again. Germany, a country with a long history of anti-nuclear movement, went back and reversed a previous decision to phase out nuclear power. France signed nuclear cooperation agreements with countries in Africa and the Middle East. “It is time for this country to start building nuclear power plants again”, proclaimed US President Bush in June 2005. The Nuclear Renaissance was in full swing.

Fukushima, 11 March 2011. Following a major earthquake of magnitude 9.0, a 15-metre tsunami disabled the power supply and cooling of Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant reactors, causing a nuclear accident. The plants were not built to handle an earthquake and tsunami of that magnitude possibly leading to under-engineering of the backup systems. This caused the loss of these plants, radioactive contamination of a large chunk of Japan, and a general downturn in public acceptance of nuclear power. A few months later, Germany came to a dramatic U-turn, announcing they’d bring the use of nuclear power to an end by 2022.

Since then, solar and wind have mostly engrossed the interest, as their costs are continuously declining and their power generation is skyrocketing. For years, nuclear power seemed stagnant in the West. Is this about to change, though?

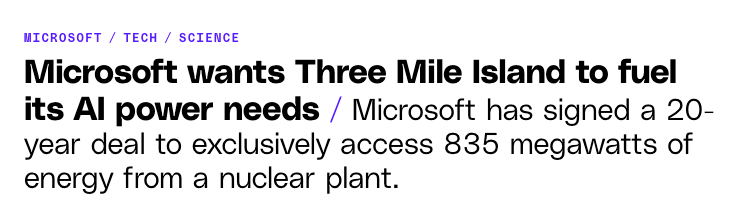

This literally came in as I was writing this piece:

Microsoft just signed a deal to revive the shuttered Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. If approved by regulators (US-NRC), Microsoft would have exclusive rights to 100% of the output for its AI data centre needs.

In parallel, Amazon Web Services (AWS) is looking to hire a principal nuclear engineer to work with external partners and influence the design of "operationally efficient and safe modular nuclear plants" to support AWS’s growing cloud power demands. Oracle founder Larry Ellison also revealed that his company planned to build a 1 GWe data centre campus backed by three nuclear small modular reactors.

So, is nuclear making a comeback? What are small modular reactors (SMRs) that seem to be leading this?

In Part II, we will dive into the future of nuclear power, the latest technological advancements in the industry, and how Greece can add nuclear power to its energy mix, with nuclear physicist and president of the Deon Policy Institute, Dr. Georgios Laskaris.

Jobs

Check out job openings here from startups hiring in Greece.

News

Syft Analytics (accounting tech) acquired by Xero for $70m.

Manual (men’s healthcare provider) secured £29.2m.

Simpler. (e-commerce tech) raised €9m.

Vivian Lab (women's health platform) raised €300k.

Quantum Signals (quantum tech for finance) raised funding.

Compellio (asset tokenisation) raised funding.

Ena Athletics (performance sportswear) secured funding.

Kinisis Ventures (fund in Cyprus) announced Fund II.

Alter Ego Ventures (fund in Greece) launched with €10m.

Resources

Lessons learned raising six funding rounds by Alex Loizou, co-founder of Trouva.

Building an information services firm to shape better business decisions with George Tsarouchas, co-founder & CEO of Dialectica.

AI Challenges: Overfitting with Dimitrios Markonis, Data Science Manager at Intelligencia.

How to make the first open source contributions by Stavros Panakakis, Tech Lead at HelloWorld.

From Dependency Inversion to Dependency Injection in Python by Antonis Markoulis, Staff Software Engineer at Orfium.

Events

“Open Coffee Athens #119” on Oct 3

“Betterways 2024” on Sep 27

“Meet Greece Startup Ecosystem” by Founder Institute Greece on Oct 1

“START your night UP” by Envolve Entrepreneurship on Oct 2

“GenAI Summit Europe” on Nov 18

Thanks for reading, and see you in two weeks. If you’re enjoying this newsletter, share it with some friends or drop a like by clicking the buttons below ⤵️

Find me on LinkedIn or Twitter.

Thank you so much for reading,

Alex

Great overview on nuclear. Look forward for the second part.