Quantum Cameras for Space

Next-gen vision powering satellites and machines

This is Startup Pirate #129, a newsletter about startups, technology, and entrepreneurship, featuring scoops, jobs, and interviews with the most influential Greeks in tech. If you’re not a subscriber, click the button below and join 7,000 readers.

Quantum Cameras for Space

In 1997, a computer beat the world’s best chess player.

For one eight-year-old watching from Crete, it marked the realisation that intelligence wasn’t confined to humans and that machines might one day see the world very differently than we do. Fast forward a couple of decades, Johannes Galatsanos and Diffraqtion question something even more fundamental: how machines observe reality in the first place.

Nearly every modern system, from satellites and drones to cars and robots, still relies on a centuries-old idea: capture an image, then try to understand it. Quantum physics suggests that this approach may be deeply inefficient.

What happens if you flip it around? I sat down with Johannes a few days after Diffraqtion emerged from stealth with a $4.2M pre-seed round to explore a new way for machines to see, one that could quietly reshape everything from space infrastructure to physical AI.

Let’s get into it.

Alex: Johannes, I’d love to start with your personal journey because I think it’s interesting how you ended up at a space tech company that blends quantum, photonics, and AI.

Johannes: I grew up in Agios Nikolaos, Crete, and as a kid, I was an avid chess player. When I was eight, Garry Kasparov lost to IBM’s Deep Blue. I remember watching the match with my chess trainer and realising that a computer had just replaced me. At the time, it felt like my future career was dying in front of me.

But that shock quickly turned into fascination. I wanted to understand how machines could think and how far that could go. I started coding early and then studied computer science and AI at the University of Frankfurt. This was in the early 2000s, well before AI became mainstream. I worked on early AI systems for board games; similar research that was eventually pursued by DeepMind and evolved into AlphaGo and AlphaZero.

Academia is incredible, but for me it wasn’t the right long-term fit. I moved into industry and worked on applications such as drone automation in energy, AI-driven manufacturing inspections in Germany, and, later, large-scale data science platforms. One defining chapter was at Novartis in Switzerland for six years, where I built a data and AI organisation from scratch, growing it from zero to about 200 people. By the end, we were supporting almost every division in the company.

In 2022, I decided to look for a breakthrough technology I could spin out of a university. I went to Oxford for a mid-career degree and then to MIT, where I worked as a quantum researcher. That’s where I met my co-founder, Saikat, who was leading the Centre for Quantum Networks. One day, he told me, half-jokingly, that he was “looking for aliens with a camera.” He’d spent seven years working with NASA on imaging systems designed for the Habitable Worlds Observatory, the largest telescope ever built, searching for exoplanets and signs of life.

I immediately saw the opportunity: what if you took that camera and pointed it somewhere else? In late 2024, we raised non-dilutive funding from DARPA (the R&D agency within the U.S. Department of Defence) and, a couple of months later, brought in Christine, a Harvard PhD in Physics with research spanning quantum, optics, information, and defence, as CTO.

Alex: Would love to learn more about Diffraqtion’s underlying technology and how this compares to existing solutions we have for space and earth observation?

Johannes: It helps to step back and look at how cameras have worked for almost two centuries. At a fundamental level, today’s advanced digital sensors follow the same principle as 19th-century photography: light hits the film (or sensor), you capture an image, and then you try to extract information from it.

That approach is intuitive, but it’s inefficient from a physics perspective. Quantum mechanics tells us that the moment you observe light, you disturb it. By forcing photons into an image, you collapse their quantum state and throw away an enormous amount of information in the process. You can lose anywhere from 95% to 99% of the information carried by the light before you ever start processing it.

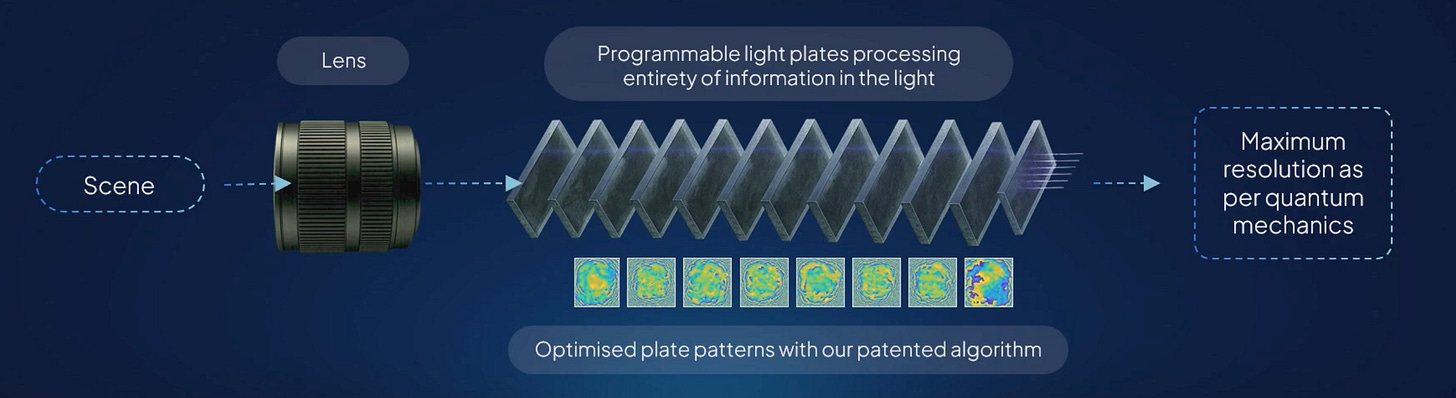

Our camera takes a different approach. Instead of forming an image first, we process the light as it arrives. The photons are manipulated optically, before they are measured, and only the result of that computation is observed. In other words, observation happens at the very end of the pipeline, not at the beginning. That lets us preserve almost all the information.

This change has profound consequences. By delaying observation, we break what’s known as the diffraction limit, the fundamental resolution limit of conventional optics, and achieve what’s called sub-diffraction imaging. In practical terms, that means we see up to 20-25 times farther away than traditional cameras.

Equally important is how the processing happens. The camera itself is not just a sensor; it’s a processor. More specifically, it’s a photonic processor. Instead of using electrons, transistors, and clock cycles like a GPU or CPU, it computes using light itself. That means the processing happens at the speed of light and with dramatically lower energy consumption.

What comes out of the camera, then, is not necessarily a photograph in the conventional sense. It’s information. Depending on the algorithm running on the photonic processor, the output might answer questions like: Is there one object or two? Is this a star or a planet? Is this a car, a truck, or a ship? You program the camera much as you would a visual AI model, but the computation occurs directly in the optical domain.

The result is a system that is fast, lightweight, and energy-efficient, while also being far more information-rich than conventional imaging. In applications where speed, resolution, and power constraints matter more than producing a human-readable image, this approach is essential. It’s fundamentally more aligned with how nature itself encodes information in light.

Alex: Why are you starting with space, and what use cases are you prioritising at the moment?

Johannes: Space is the harshest environment imaginable. That forces innovation. Historically, many of the technologies we rely on today, like GPS, the internet, and semiconductors, were first developed for space or defence.

But there’s another reason: economics. If you improve the resolution by 20 times, you can make the lens 20 times smaller. In space, that cascades. A smaller lens means a dramatically smaller satellite, and satellite cost scales exponentially with size. A satellite that normally cost $100 million could cost under $1 million with this approach. That kind of 100x improvement doesn’t exist in other industries.

At the same time, there’s been a surge in demand for sovereign space capabilities. For a long time, much of the world relied on a small number of providers, primarily the United States, for high-quality Earth observation and space intelligence. That model is changing. European countries are investing in sovereign constellations, while China has expanded its space capabilities at an extraordinary pace. The result is a much more multipolar space environment.

Space itself has become contested. Satellites are no longer assumed to be safe once they reach orbit. Jamming, spoofing, cyberattacks, and even kinetic threats are now part of everyday reality. Every serious conflict today has a space dimension, because whoever controls or disrupts the “eyes in the sky” gains a major strategic advantage. Defence is currently our largest market, but commercial applications such as agriculture, energy infrastructure, and logistics will grow rapidly as costs decline.

Alex: Will you build your own satellite constellation?

Johannes: We’ll do both. We can launch our own small satellites, 6U CubeSats about the size of a backpack that are hard to detect, which is great if you run sovereign constellations, or fly as a hosted payload on larger platforms, which is cheaper, but you don’t decide the orbit. The key point is that we own the camera and the data. We don’t sell the quantum camera itself. We sell analytics derived from it.

Alex: Where does this technology go from here? Do you expect every physical AI device to need such a camera in the future?

Johannes: By 2030, there will be billions of devices with physical AI — robots, drones, cars, satellites, etc. Almost all of them benefit from faster, more precise vision and processing, e.g., for obstacle detection. Right now, our technology is expensive because it’s early. Eventually, it becomes cheap enough to put it everywhere. And when that happens, the use cases will explode in ways we can’t yet predict, just like nobody predicted when semiconductors were invented that we’d be watching cat videos on YouTube.

Alex: I came across some research you published on the state of quantum technologies (readers can find it on arXiv here). What are the technological breakthroughs you think will accelerate the deployment of quantum technologies, and would you expect these to come from the West or China?

Johannes: It’s helpful to start by clarifying that “quantum” isn’t one single technology area. There are three major pillars. The first is quantum computing, which gets most of the headlines and hype. The second is quantum networks, focused on secure communication. And the third (where our work sits) is quantum sensing, which is about measuring the physical world with unprecedented precision.

These areas are connected, but they mature at very different speeds. Quantum sensing is the most immediately practical. You’re usually measuring one physical phenomenon, rather than orchestrating thousands or millions of fragile quantum states the way a quantum computer requires. Because of that, many sensing technologies have already moved out of the lab and into real systems, like GPS or MRIs.

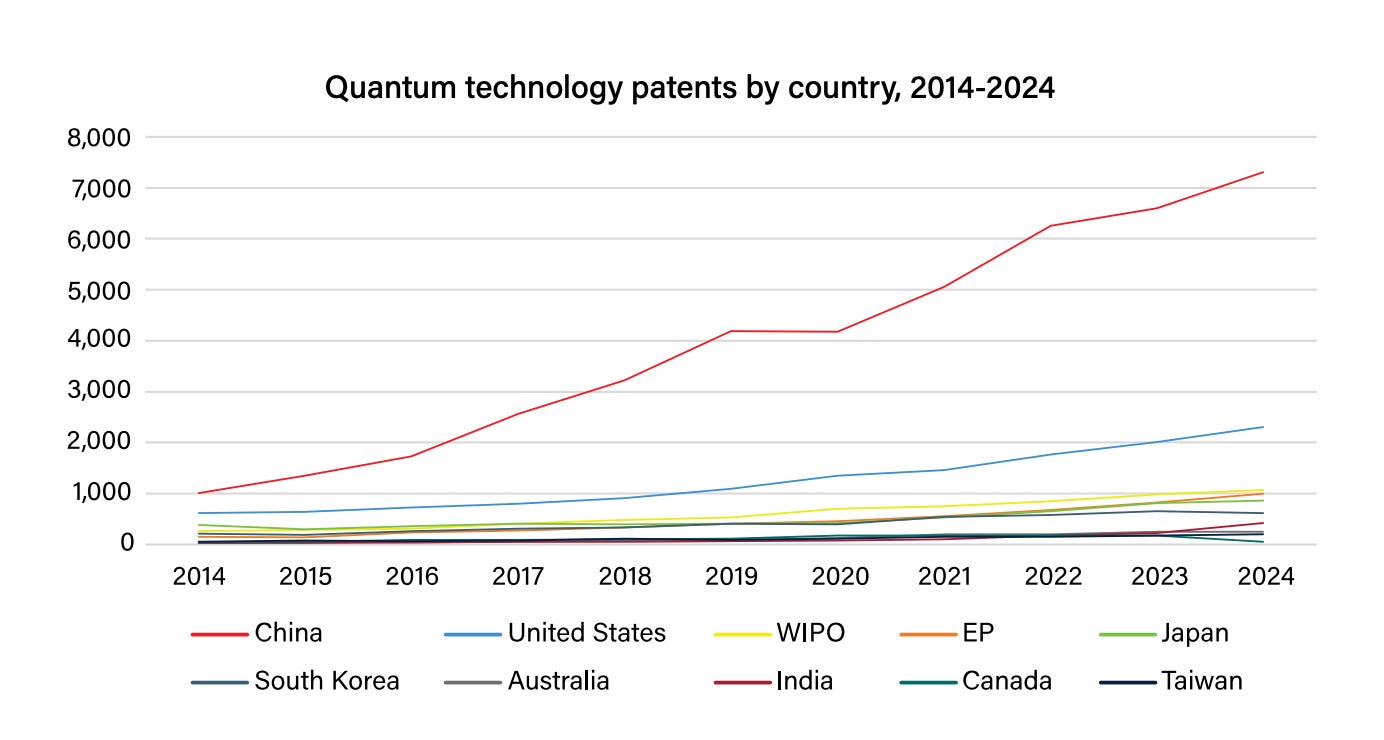

Geographically, the picture is more complex than a simple East-versus-West narrative. In photonics and optics, the foundation of many quantum sensing technologies, China is already extremely strong. If you look purely at published research, patents, and university rankings in optics and photonics, many of the top institutions are now based there. A large share of global output in these fields already comes from Chinese labs, which are also ahead in commercialisation. It’s only a matter of time before we see amazing photonic devices in quantum computing from China.

The United States and Europe still lead in several critical areas, particularly in system integration and building startups that translate research into deployable products. There’s also a strong ecosystem effect: venture capital, defence partnerships, and early customers play a huge role in turning quantum research into something real.

What’s important to understand is that we’re no longer waiting for a single scientific breakthrough. The physics is largely understood. The challenge now is engineering: making these systems smaller, more stable, cheaper, and scalable. That kind of progress tends to come from sustained investment, manufacturing capability, and iteration, not from one dramatic “eureka” moment.

As a result, breakthroughs will almost certainly come from both sides. Different regions will lead to different layers of the stack. Some advances will be visible through publications and startups; others will happen quietly, especially in defence or classified programs, where nothing is published at all.

Ideally, these advances would drive collaboration. Quantum technologies have the potential to improve sensing, medicine, communications, and scientific understanding, benefiting everyone. But the reality is that the current global trend is toward competition rather than cooperation. Space, quantum, and AI are increasingly seen as strategic assets.

That tension will shape how the technology evolves. But regardless of where individual breakthroughs originate, the pace of progress is accelerating. Quantum sensing, in particular, is moving from “interesting physics” to “useful infrastructure,” and that transition will reshape multiple industries over the next decade.

Alex: That was so much fun and inspiring, Johannes! Thank you.

Join a Startup

Job opportunities you might find interesting:

Headquarters Health (concussion care): Founder’s Associate w/ visa sponsored to relocate to SF

Mobito (vehicle data solutions): Applied Geospatial Data Scientist

Lifebit (precision medicine data): Executive Operations Manager

Keragon (no-code healthcare operations): Integrations Software Engineer

Workable (HR tech): UX Data Analyst

Fundings

LMArena raises $150M at a $1.7B valuation, scaling its anonymous, crowdsourced LLM benchmarking platform; backers include Felicis, a16z, Kleiner Perkins, Lightspeed, and more (founded by Anastasios Angelopoulos).

Orbem closes a €55.5M Series B led by Innovation Industries with General Catalyst, 83North, and others to apply AI and MRI to food and biological systems (founded by Maria Laparidou).

balena lands growth investment from LoneTree Capital to expand its IoT device management platform; founded in 2013 as Resin.io by Alexandros Marinos and Petros Angelatos, now co-led by Konstantinos Mouzakis.

Elyos AI secures a $13M Series A from Blackbird Ventures, Y Combinator, and others to deploy AI agents for trade and field services (founded by Panos Stravopodis).

United Manufacturing Hub raises €5M led by KOMPAS VC for its industrial data management stack (founded by Jeremy Theocharis).

Arc Simulations announces a £1.5M Seed to bring ball-tracking tech to sports, starting with cricket (founded by Michael Armenakis).

CLEAN i.T secures a €413K round led by Investing For Purpose to scale its cleaning services platform (founded by Evelina Mavrides).

M&A

Defence company Theon International (AMS: THEON), founded in 1997 in Greece by Christian Hadjiminas, which manufactures night vision, thermal imaging, and electro-optical ISR systems for military and security applications, acquires a 9.8% stake in Exosens SA for €268.7M.

Bugcrowd acquires Mayhem Security, the AI offensive security startup founded by Thanassis Avgerinos, folding automated attack tooling into the crowdsourced-cyber leader’s platform (Bugcrowd has raised $230M+).

New Funds

Niko Bonatsos leaves General Catalyst to launch a new early-stage fund called Verdict Capital, targeting $300M size.

Metavallon VC launches Brain Gain Fund, a new €5M pre-seed fund deploying €200K-€400K per investment.

Events

Open Coffee Athens, Jan 23. RSVP here.

Open Coffee Thessaloniki, Jan 23. RSVP here.

Greeks In Tech London, Jan 30. RSVP here.

Greeks In Tech Zurich, Feb 20. RSVP here.

That’s a wrap, thank you for reading! If you liked it, give it a 👍 and share.

See you in two weeks.

Alex

Thanks for writing this, it clarifys a lot; what if this quantum "flipping" of observation allows AI to model and interact with the physical world not just more efficiently, but with a fundementally different, perhaps richer, understanding of its underlying quantum states?

Fantastic deep dive into quantum sensing applications that finally makes the physics intuitive for non-specialists. The idea that conventional cameras throw away 95-99% of photon information before processing even begins is mind-blowing. I've been following the space observation sector and the cost reduction potential from smaller satellite optics is definately where the commercial opportunity lies. Dunno if photonic processing scales to consumer devices by 2030 but the trajectory seems plausable.