Grocery Delivery Models

Grocery delivery economics and flywheels: there cannot only be one, SEO principles, funding news, jobs, effective job descriptions and more

👋 Happy Friday! Welcome to Hunting Greek Unicorns #32. I’m Alex, a product guy turned VC, and every two weeks I send out a newsletter with everything you need to know about the Greek startup industry.

📬 If you find this newsletter interesting, consider sharing with your friends or subscribe, if you haven’t already, and join a community of 2,467 Greek startup enthusiasts.

🔍 Grocery delivery models, economics and flywheels: there cannot only be one

The grocery delivery space in Europe is crazy 🔥 right now! Startups are becoming unicorns in months, they launch in new cities and countries overnight, they raise billions of money, and acquire smaller startups to boost expansion. What’s happening in Greece? The industry is growing fast with some serious upside. Right now, existing players (brick and mortar sellers and established startups) are dominating the market experimenting with different models and partnerships. Well, that’s about to change!

To explain the frenzy in grocery delivery, I decided to team up with Marko Tsirekas, Head of Product at ZOE, founder, and long-time marketplace builder. In this post, we go deep in the economics of the sector, look at the different business models, discuss how the wave looks like in Greece and who is an emerging player that is coming out today with a pre-seed funding round and is ready to go after the market. Let’s get to it.

Riding the speedy grocery delivery craze

Billions have been invested in the market in the past 12 months across Europe. In the list of recently funded startups you can also find the current fastest unicorn in the continent. These are just some of the news announced the past months:

Gorillas raised a €245m Series B, making the company a unicorn just nine months after launch and the fastest European tech company ever to reach unicorn status. They’re already planning for another $1b round with a $6b valuation.

Getir has raised almost $1b the past four months with its latest Series D reaching a valuation of $7.5b (only six months after expanding outside Turkey).

Flink launched six months ago and just raised $240m.

Glovo raised Spain’s largest ever funding round with €450m and plans to operate around 200 dark stores by the end of 2021.

One of the biggest US startups in the sector Gopuff (raised $2.4b so far) entered Europe with the acquisition of Fancy in the UK.

Oda raised €223m to expand beyond Norway, to Finland and Germany.

Rohlik picked up €190m to further expand in existing markets and break into Germany, Poland, Romania and other countries.

Everli, with operations in Italy, Poland, Czech Republic and France, raised $100m in Series C funding.

You get the point. Yes, the overall funding landscape is overheated, yet the above is too overheated. Why is this happening? What do investors see? How does this online groceries model work?

From groceterias to dark stores

Perhaps it helps to understand how supermarkets started. It all started back in 1859 in New York City, where initially single-item stores were combined into “groceterias”; grocery stores which resembled eateries like the name suggests where variety was introduced. This model worked and gave rise to the chain stores, but it wasn’t until the 1950s when the idea of a supermarket was realized. In truth, supermarkets, almost an institution in our lives, lacked any creative flair; they were byproducts of the macroeconomic factors. Specifically, two trends: urbanization and investment in the logistics infrastructure.

Supermarkets became a smash hit for a simple reason. The more items, the more the use cases, the more the clients. It’s a win-win. At the same time, processed foods became mainstream, which further increased the supermarkets’ margins. Hence, supermarkets kept getting bigger, adding more aisles and getting more efficient. In doing so, revenues consistently grew and the original relationship between the grocer and the client was diluted to the self checkout we know. This does not come without cost. Storing every single item to attract the majority of the population comes with storage, waste, labor and logistic costs. And the supermarket profitability curve matured somewhat like this:

The basics of the revolution we are experiencing now are not so dissimilar. The next wave of urbanization (what we understand as big city living today) and logistical innovation (think Amazon) gave birth to the “on demand economy”. The likes of Uber, DoorDash and TaskRabbit were wild successes by providing a layer of servicing customers wanted. And so the obvious idea arose: what if this was applied to groceries? But this time around, both entrepreneurs and VCs were cautious of the learnings of the previous era. We learned that the on demand model has appeal but does not come without risks. Where Uber and DoorDash won, many others failed. And so the lesson was learned: blitzscaling with negative unit economics does not come without risks. This is where the promise of the new on demand wave around groceries differs. The consumer proposition is simple: Great reliability, availability and speed without the aforementioned risks. The customer relationships are once again human by default and purchases are repeated. And dark stores were born.

Unlike supermarkets, on demand groceries don’t need to have everything. They understand that fundamentally their value is on availability, not variety. This means less fresh items, less storage and a ruthless focus on profitable items. That is not it though. Unlike supermarkets, which need to cater both for a visual experience (aisles) and double as a micro-fulfillment center, dark stores are optimized for deliveries and have significant gains in three crucial metrics: cost/sq.ft, space/item and packing/hour. The final bit is not obvious, yet is important. Since the items are not laid out to fulfil aisles, coca cola and gummy bears might be stored next to each other if they’re likely to be purchased together and therefore easy to be packed together.

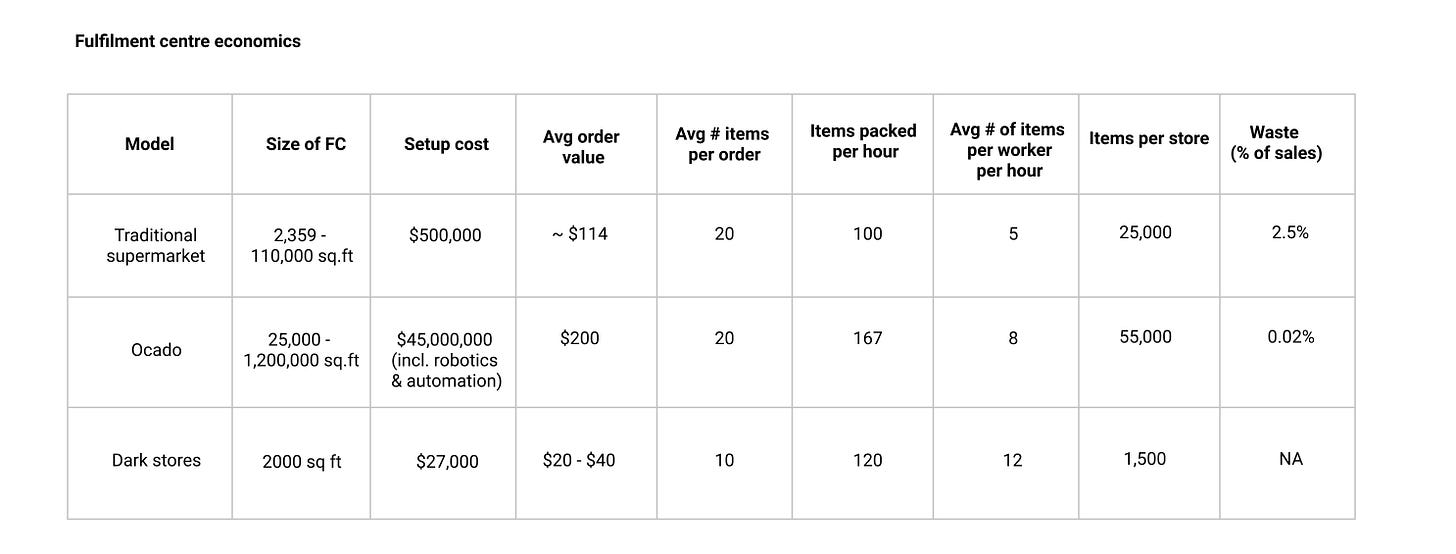

If you’re now thinking “What about warehouse management systems and robotics, surely that’s expensive” you’re right. This is the Ocado way: the pioneer in robotics applied in the warehouse and leader of online grocery shopping. But, in this model, it is not necessary. Whilst this smart warehouse platform comes with gains in packing, it assumes a very high capital expenditure. Around $45,000,000 to be precise. In contrast, a dark store requires upfront capital expenditure of about $20,000.

In terms of revenue, the gross margins stay the same across models ranging from 30% for branded FMCGs to 50% in private labels. Though, the critical point is that “top up” purchases (or the “order when you need them” model) do not reach the $140+ basket. So what is the reasoning for it? That supply will force the habit, leading to an increased number of orders per week (instead of planning in advance and ordering the groceries for a week or two), which is also what happened in previous on demand waves. Here is what we have so far in the dark store operating model:

low set up costs

a ruthless focus on a segment with high disposable income

high gross margins and efficiency gains inherent to the set up

a huge market, free of winner takes all dynamics

relatively low CapEx and opEx.

What is missing? Differentiation. Does it matter? No, because the market is so big that any given player only needs to win a few places and just like with our groceterias enter the buyout pageant.

The other side of the table: the aggregator

On the other side of the table sits a different kind of beast. The aggregator. One which follows the steps of the first on demand players and has a rather different view on the market that is simple and goes like this: attention is all you need and thus, the grocery value chain surplus is in the aggregation layer, not in production or retailing. Why compete against so many existing players if margins can be realized from charging customers fees and passing on parts of the cost to retailers? The playbook can be summarized as: scale fast, become the aggregator and then terms are imposed and additional revenue streams arise. This is the aggregator way. This is the way of Instacart. These players are equally after gross merchandise volume as much as they are after attention. Once they control attention, they don’t just control the customer’s wallet; they also control the advertiser’s budget. Here is an example from Instacart, perfectly executing on this point by having featured products inside stores:

Positioning oneself as a service layer bringing on demand availability requires no warehouse to begin with. It does however require fast scale and local continuous optimization across the organization to achieve local network effects. In essence, it’s a three sided marketplace. Not an easy task.

The landscape of grocery delivery in Greece

What does the market look like in Greece? The market boomed last year and still has a lot of space to grow. To give you an idea, according to Convert Group, the turnover of online supermarkets grew 262% in 2020 (the growth rate was 33% in 2019), reaching 1.8% of total grocery sales (up from 0.4% in 2019). Imagine that last year in the UK, the online supermarket % turnover reached 11.5% according to Kantar. There’s some serious upside here both for existing and new players. The landscape includes online arms of established brick and mortar sellers in the likes of AB, Sklavenitis, Masoutis, etc along with startups such as efood, Delivery.gr, Box.gr, Wolt, e-Fresh, and others. In Greece, it’s much easier for players to flex from one model to another (dark stores vs. marketplace) as they have less competition to worry about and easier to meet consumer demands and in fact we have examples of that happening in the past. Let’s take a closer look at two of them:

efood (acquired by Delivery Hero in 2015) had an overall turnover of 64.4m euros in 2020, a figure increased by 49% compared to 2019. They ventured into groceries through partnerships with other stores (including the large supermarket chain Sklavenitis), as well as its own network of fulfilment stores (efood Market). Konstantinos Giamalis, CPO of efood, also pointed out the company’s interest for on demand groceries in one of the previous Hunting Greek Unicorns talking about quick commerce.

“... A nice example is QCommerce or quick commerce, where users are able to order their groceries, etc. conveniently & fast. We are transforming our business model to accommodate Qcommerce although it has a relatively smaller share than food orders, and lower margins than a pure food delivery marketplace…”

In addition, Paminos Kyrkinis, CEO of efood, recently mentioned in an interview that they’re aiming to deliver all orders in less than 10 minutes and their vision is to develop quick commerce and become the largest on demand shopping service in Greece.

It will be interesting to see how the recent launch of InstaShop (acquired by Delivery Hero in 2020) in Greece, starting with the city of Thessaloniki, plays out given both efood and InstaShop belong to the same group now. InstaShop is focusing on the marketplace model promising 30 to 60 minutes deliveries depending on location.

Wolt is a Finnish startup founded in 2014 that has raised over $822m. They launched in Greece around 2.5 years ago and they now also operate in grocery delivery with around 10% of its stores in online groceries. Their overall turnover increased 14x in 2020 with a volume of 7.2m euros. They recently launched their first dark store in Athens (Neos Kosmos) with the name “Wolt Market”.

These are just a few of the Greek teams operating in the sector. As global grocery delivery is booming and the local market is still in its infancy, it is expected to see new players emerge. So here we are, with a new promising team coming after it!

Ferto: a new player emerges

Ferto is coming out today with a pre-seed round of funding of 400K euros. The company launched earlier this year with the aim to deliver products from local retailers (super markets, grocery, meat, flower, pet shops - anything really) in 20 minutes with their own fleet of riders. They started operations in the south part of Athens, deepening the network effects in that area with exclusive partnerships and are planning soon to expand in more locations around Athens. Moreover, the founding team is bringing experience from some of the most high-growth Greek startups (in fact, Michael Sfictos is the co-founder of Taxibeat, exited to Daimler some years ago).

Ferto is joining the race at a very interesting point. The pandemic tailwinds have accelerated, perhaps even inflated, the perceived need of a widespread last mile logistics infrastructure. Incumbents are being pushed to evolve their offering (Sklavenitis, AB, Masoutis, Kritikos already established partnerships with food delivery startups), supply of capital from investors is growing and unicorns will soon need to expand in other countries to meet their goals. The perfect storm for a company like Ferto. A strong commercial team, a market which is big and still growing and already established players, traditional or digitally native, vying for market share. At first, this makes the field look quite competitive. This would be a problem, yet in this space, this might be a relentless land grab game, but not one where the winner takes it all.

VCs know it, incumbents know it, and Ferto knows it too. Their goal is clear: scale as fast as possible and their horizontal positioning is key to that goal. After proving traction, the next step is to attract more investment to speed up their growth rate and establish loyal customer relationships. Then optionality is possible. Either decide to reduce operating cost by centralizing operations, having studied the on demand grocers of EU, or become a provider of services empowering retailers that don't want to pay the steep costs imposed by incumbents. There is a tricky point in this journey. Scaling the marketplace is a great tactical move to start, not a long term play. As much as the potential for growth is great, Greece is not big enough in itself nor can it be a gateway to other markets for groceries. To add to that, advertisers are still spending less in performance marketing in comparison to other markets, which has proven to be a key for service providers such as Instacart to improve their margins structure.

If these scenarios start becoming intricate and the nuances around the models complex, here’s the gist: in the end all the players go after the same revenue streams. This can only mean one thing: wars and buyouts. On the one hand we have the vertically integrated retailers who focus on dominating pockets of cities, on the other hand we have the wildly ambitious service led marketplaces that play the too big to fail game. Somewhere in the middle are the behemoths of groceries waiting to attack. It's a bull market and it's just getting started.

🦄 Startup Jobs

👉 The Greek startup industry is heating up! If you’re still watching from the sidelines, start your job search here. A list with 845 handpicked opportunities waiting for you to apply. Company data is also available.

🗞️ News

Code BGP, a startup building a better and more secure Internet by modernizing operations for Internet network operators, announced a Seed round of $1.5m from Marathon Venture Capital. The company is a spin-off of Foundation for Research & Technology-Hellas (FORTH).

Hellas Direct, an insurance tech company operating in Greece and Cyprus, raised €32m in funding. Next steps for the team are to expand its offering and establish in five more European countries.

Honest AI, a real estate data intelligence platform, secured funding from InnovateUK, a grant funded by the UK government.

ESA BIC Greece (the European Space Agency business incubation centre of Greece) is accepting applications until the 28th of June here.

Life Sciences are the leading fields of activity in startups registered in the Elevate Greece platform.

The three winners of this year’s Envolve Award Greece are the following startups: Carge, Momcycle and obko.

Optistructure, Docandu, Gaming Brotherhood, Time is Brain, Kleesto, 12GODS, Robenso, EDEN, EV Loader and φwater were the winners of the Innovation & Technology competition organised by NBG Seeds.

💡Startup Profiles

🤓 Interesting Reads

An interesting analysis on the current state of the Greek startup industry by Sifted. Greece is back, for good!

A deep dive into the SEO principles followed by Skroutz. An important pillar of how it has ended up being the fourth most visited site in Greece at the moment, by Vasilis Giannakouris, SEO Lead at Skroutz.

More SEO insights by John Short, Founder of Compound Growth Marketing.

A post on appreciation and recognition within teams by Petros Amiridis, Head Of Support at GitBook.

How to write effective job descriptions by Zaharenia Atzitzikaki, Design leader and previously VP Design at Workable, here.

Alex Chatzieleftheriou, co-founder & CEO of Blueground, discussing the company’s Work from Anywhere policy, or Blueground Nomads, on Forbes.

🎧 Podcasts

A discussion on Ethereum with Georgios Konstantopoulos, Research Partner at Paradigm, Elias Simos, Protocol Specialist at Coinbase, as well as Vitalik Buterin, one of the co-founders of Ethereum.

Thanos Bismpigiannis, Head of Product at Plum Fintech, discussing career ladders in product and how to become a great product leader.

Stavros Papadopoulos, founder & CEO of TileDB, and Norman Barker, VP of Geospatial of TileDB, on TileDB, managing geospatial data and more, here.

A podcast with Dimitris Glynos, CTO of Census Labs, at BadGuys talking about all things security.

🍕 Events

An interesting event coming up from the Greek tech community:

“First Ever Monthly PyGreece Meetup” by PyGreece on June 30

I’d love to get your thoughts and feedback on Twitter or Facebook.

Stay safe and sane,

Greek Startup Pirate 👋